‘Carraig Aonair’: An Eighteenth-Century Elegy

Topography and Theme

From Clear Island (Cape Clear), the approximate distance to Fastnet Rock is six and a half kilometres. The islet lies roughly thirteen kilometres from the West Cork coast. ‘Carraig Aonair,’ as Fastnet is known in Irish, means ‘lone rock.’ That place name serves as the title of a noted lament in the Irish language, spoken by a father for three sons and a son-in-law who drowned while fishing near Fastnet. It is attributed to an O’Donoghue from Aghadown by Thomas Crofton Croker (1824), and by Selina Martin (1844). Martin dates its composition to approximately 1784.

Given that ‘Carraig Aonair’ originates in the oral tradition, the poem’s title is not one prescribed by an author. The popular title it has gained reflects reciters’ and listeners’ engagement with the narrative. Carraig Aonair as place name ostensibly frames the islet in relation to ocean surrounds. Its appeal as a title for this elegy is derived from this connotation of vast ocean expanse. The sea’s great force is a presiding feature of the atmosphere of helplessness which pervades the poem.

The track of legendary Cúil Aodha singer Diarmuidín Ó Súilleabháin performing ‘Carraig Aonair’ is playable at the SoundCloud link below. In Leabhar Mór na nAmhrán (Ó Ceannabháin et al., 2013), an anthology comprised of 400 sean-nós songs, each with accompanying annotations, a complete printed version is available.

Some Characteristic Features of Keening

The elegist asks of his children – ‘Ó, a chlann óg mo chroí’ (‘O, my darling children’; my trans.) – whether they pity his distressed state, ‘ag géarghol is ag caí’ (‘bitterly sobbing and weeping’; my trans.; Ó Ceannabháin et al., 2013, p.318). To make a direct address to the deceased is typical of a keen’s beginning, as outlined, for example, by Breandán Ó Madagáin (2005, p.81). This vocative affirms the typicality of ‘Carraig Aonair’ as caoineadh, and marks it a particularly moving example, owing to the emphasis on the sons’ youth.

Conventions of the caoineadh tradition, specifically the vaunting of physical strength and generosity of spirit, subtend the mourning of Donncha and Cormac. Donncha’s excellence as provider is detailed admiringly: ‘bhíodh an fia aige ón gcoill, agus an bradán ón linn’ (‘he used to catch deer from the woods, and salmon from the pool’; my trans.; p.318). Praise for Cormac also amounts to the image of a son kindly and strong, but finds more prosaic expression: ’Do bhí sé modhúil múinte, ó, lúfar go leor’ (‘He was mannerly, polite, and very athletic’; my trans.; p.318 ).

Only Dónal’s remains came ashore after the drowning. A description of his lifeless form contrasts starkly with the foregoing images of vigour:

Gan tapa gan bhrí, gan anam ina chroí / Ach a ghéaga boga geala is iad leata ar an dtoinn

Without vigour or energy, without spirit in his heart / His soft bright limbs aspread on the wave (my trans.; p.318).

Juxtaposition of the animation of physical form in life with its stillness in death characteristically features in the caoineadh tradition. It is memorably galling in the case of young and tragic deaths, Art Ó Laoghaire being the most famous example. In ‘Carraig Aonair,’ form is allied to trope in producing an arresting example of this contrast. The assonance of the inflected noun forms ‘bhrí’ (energy), ‘chroí’ (heart), and ‘toinn’ (wave) accents the connectedness of the sea’s power and the wasting of Dónal’s vital energies.

Two Nineteenth-Century Translations

Translations of ‘Carraig Aonair’ in Thomas Crofton Croker’s Researches in the South of Ireland (1824) and Selena Martin’s Sketches of Irish History (1844) are proffered as emblematic instances of keening. Alongside the lines cited above, one of those which best illustrates the poem’s suitability for this purpose is the speaker’s perception of proprieties of mourning:

Dá bhfaighinnse mo thriúr ‘tá go doimhin insan tsrúill / Do dhéanfainn iad a chaoineadh is iad a shíneadh in Achadh Dúin

If I were to recover the three who are in the flowing sea / I’d keen them and bury them in Aghadown (my trans.; p.319).

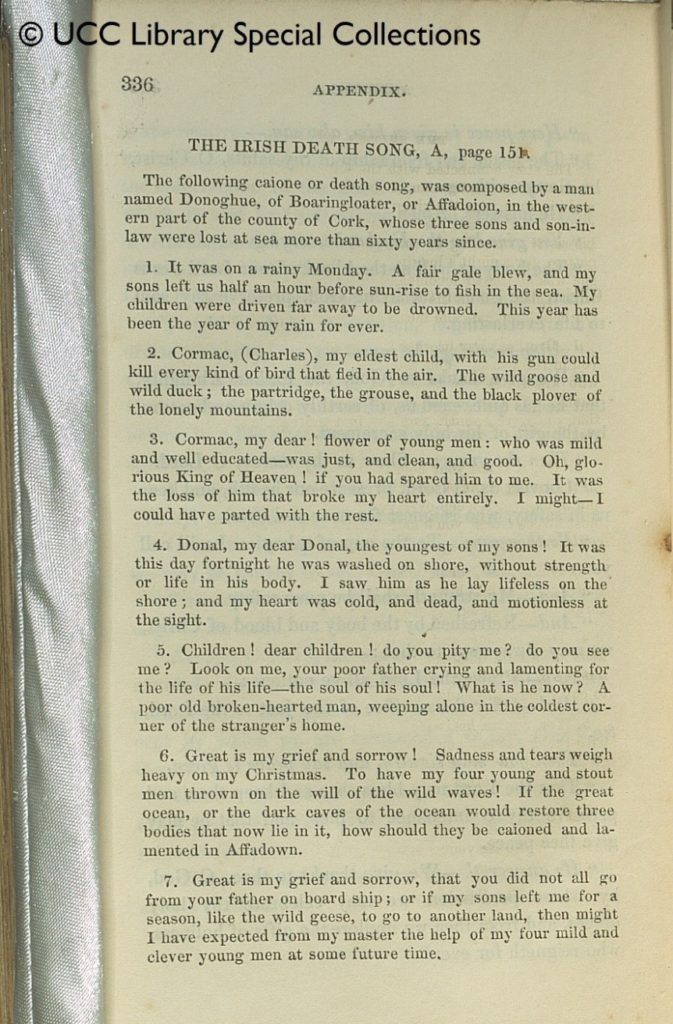

An interesting feature of both of these translations is their treatment of this particular line. In Croker we read ‘how beautifully they would be keened and lamented over in Affadown’ (1824, p. 144), whereas Martin gives us ‘how they should be caioned and lamented in Affadown’ (1844, p.336). In The Keen of the South of Ireland (1844), Croker summarily biographies the informant of his translation as a woman ‘whose name was Harrington, [and] had come from the south-west part of the county of Cork’ (1824, xxiv). Martin prefaces her own translation altogether more sparsely: ‘In the appendix will be found some literal translations from that language, with which I have been favoured by a friend’ (1844, p.151).

The particular translations of these lines tells of a subtle breakage with literal translation practice. They dispense with first person singular verb conjugations. In terms of metre, ‘Do dhéanfainn iad a chaoineadh is iad a shíneadh in Achadh Dúin’ is in fine agreement with preceding lines, as to give the sense of an uncorrupted text. In an example of a highly corrupted version, collected in 1914 from Conny Coghlan of Doire na Sagart, a reordering of this line stops short of disturbing the sense of privacy which attends first person forms: ‘Is roi-vrea mar a hinhing ‘s mar a chuinhing iad sud’ (‘I’d bury them and keen them perfectly’; my trans; Freeman, 1921, p.131). Though the importance of ritual is articulated very personally, it depends on a broader social context in order to achieve such urgency. This understanding appears to motivate the translations. Attentiveness to the backdrop of common practice of keening allows the translated texts to stand as representative of a West Cork cultural milieu.

John Woods University College Cork